What’s in a Name?

College athletics has essentially been unchanged since the beginning of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1906.

A scholarship was awarded to an athlete to cover their education. Playing the sport was practically treated as just a plus for the student in the eyes of the NCAA in terms of compensation.

Compensation was not given to anyone in any athletic department which was only an athlete in the program, other than the usual stipend checks issued to the athlete every month.

In simplified terms, the only money an athlete would receive for bringing in millions of dollars in revenue for the school, attracting thousands and thousands of fans, and drawing in countless new admissions would be scholarship money.

The same scholarship money, in some cases, is given to other students that are not athletes bringing in millions of dollars in revenue for the school.

This situation brought backlash to the NCAA, and athletes began speaking out about their wishes to be able to profit from their image in the same way the schools benefitted from their athletic ability.

On June 3, 2021, the NCAA released a statement saying that starting July 1, 2021, an interim rule would be put in place, allowing collegiate athletes to benefit from their name, image, and likeness, or NIL.

The complaints regarding NIL go back further than just recent conversations. Though it is now discussed more openly, whether athletes should be able to profit from their name has been discussed for years.

Dating back to the late 2000s, the NCAA was sued for “violation of antitrust laws” (NCAA v. O’Bannon) by only allowing athletes to be paid in scholarships and school attendance. Another case went to trial (NCAA v. Alston) on March 31, 2021, and was decided on June 21, 2021.

This sparked a big question: Is the NIL ruling good or bad?

“I think there’s merit to it, and it has its positives,” Pleasant Grove Athletic Director Josh Gibson said. “But I think it has turned into an uncontrollable beast.”

Before NIL, the NCAA had regulations allowing athletes to receive checks from their school, called stipend checks.

The stipend checks were set amounts of money that varied by the school, given to each player of the team no matter the player’s status on the roster. These stipend checks played a role in deciding to legalize the NIL rule in the NCAA.

The stipend checks usually varied from $1,300-$1,600, which also factored in to why the NCAA was so reluctant to allow players to be given such large amounts of money that, as of right now, do not have a cap.

“Even before the NIL, student-athletes at the college level were already being paid,” Texas High Athletic Director Gerry Stanford said. “Certainly not as much as now; we are talking about millions of dollars now. It is not new, it is just a new extravagance of money.”

Though the issues and dramas of an organization known as widely as the NCAA seem far-fetched to be caught up in, they do have a direct correlation to Texarkana and the athletes of our community.

Texarkana has produced an incredibly large number of division one athletes across the city from all different high schools, and we have athletes in our own backyard directly affected by NIL.

Texas High School and Pleasant Grove High School have sent athletes to universities such as Louisiana State University, Texas A&M University, The University of North Texas, The University of Arkansas, The University of Texas, Baylor University, The University of Oklahoma, and Oklahoma State University.

The NIL has opened up the realm of college athletics to unimaginable levels and has given these Texarkana athletes extraordinary opportunities to do what they love and make a living out of it, with multiple different ways for athletes to earn their compensation.

Clayton Smith, Texas High alumni, is the only five-star athlete out of the Texarkana area and is now playing at the University of Oklahoma.

On top of multiple brand deals, Smith has produced a line of his own personal merchandise sold through Fan Arch.

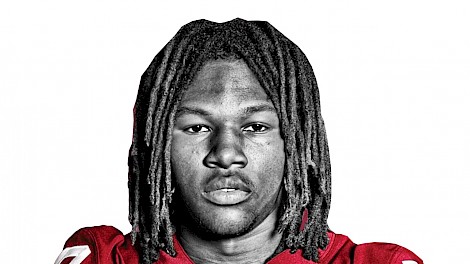

Texas High graduate and current University of Texas football player Derrick Brown is another athlete directly benefiting from NIL. Along with his brand deals, Brown profits from interactive deals, like selling in the moment autographs to fans who are out and about in Austin.

“I am glad we can profit from our name now,” Brown said. “It is a good way to get extra money in my pockets and stay close with the city and the fans.”

Pleasant Grove graduate and current University of Arkansas football player Landon Jackson is also a big name out of Texarkana feeling the love from NIL. Partnering with four brands, Jackson also profits from public signing events.

“The [NIL] definitely is something that all players at the [collegiate] level are happy about,” Jackson said. “All it is truly doing is helping athletes profit off their image while they can.”

Another Pleasant Grove alumni, Nick Martin, now playing football collegiately at Oklahoma State University, is profiting directly from jersey sales. Athletes can earn a cut of the money when fans purchase their jerseys from the school.

However, the great opportunities are accompanied by worries from the world outside of the athletes.

Essentially, college athletics is a full-time job since most athletes do not have enough time to work on top of school and their sports.

“It was very exciting just to know that I could be earning money while focusing on football,” Baylor University football player and Texas High graduate Brayson McHenry said. “A lot of people do not realize that this is a full-time job on top of school, so it is nice to be able to profit from our work.”

So, while NIL allows collegiate athletes to profit from their “job,” some people think there needs to be a cap or limit on the amount of money the athletes can make from working.

The idea of capping the amount of money that can be earned stems from many different problems that people see may arise in the future.

“I think that it has started an imbalance among universities in that the rich are getting richer,” Gibson said. “Some athletes will be valued 100 times more than another one, and that can cause dissension in a locker room where we are trying to build unity.”

In other words, a freshman rising right out of high school with zero college experience can make hundreds of thousands of dollars just for being good in high school, and people see an issue.

Another question is whether or not allowing the athletes to benefit financially from NIL will sway their team-based mindset to be a lot more selfish.

“If you win the $600 million lottery, you probably will not work much more the rest of your life; you may not work at all the rest of your life,” Stanford said. “So let’s take a true freshman coming in with nothing, and all of a sudden, he has all this money. Is he going to work as hard? Probably not. Will he keep putting in work and effort, or will he just settle?”

The bottom line is that money earned can not overrule the true reason these athletes are participating in their sport in the first place: passion.

“I think a kid deserves to get what they have worked for,” Stanford said. “I think the biggest thing on the money side of things is can the individual keep their focus on trying to improve and continue to do their best.”