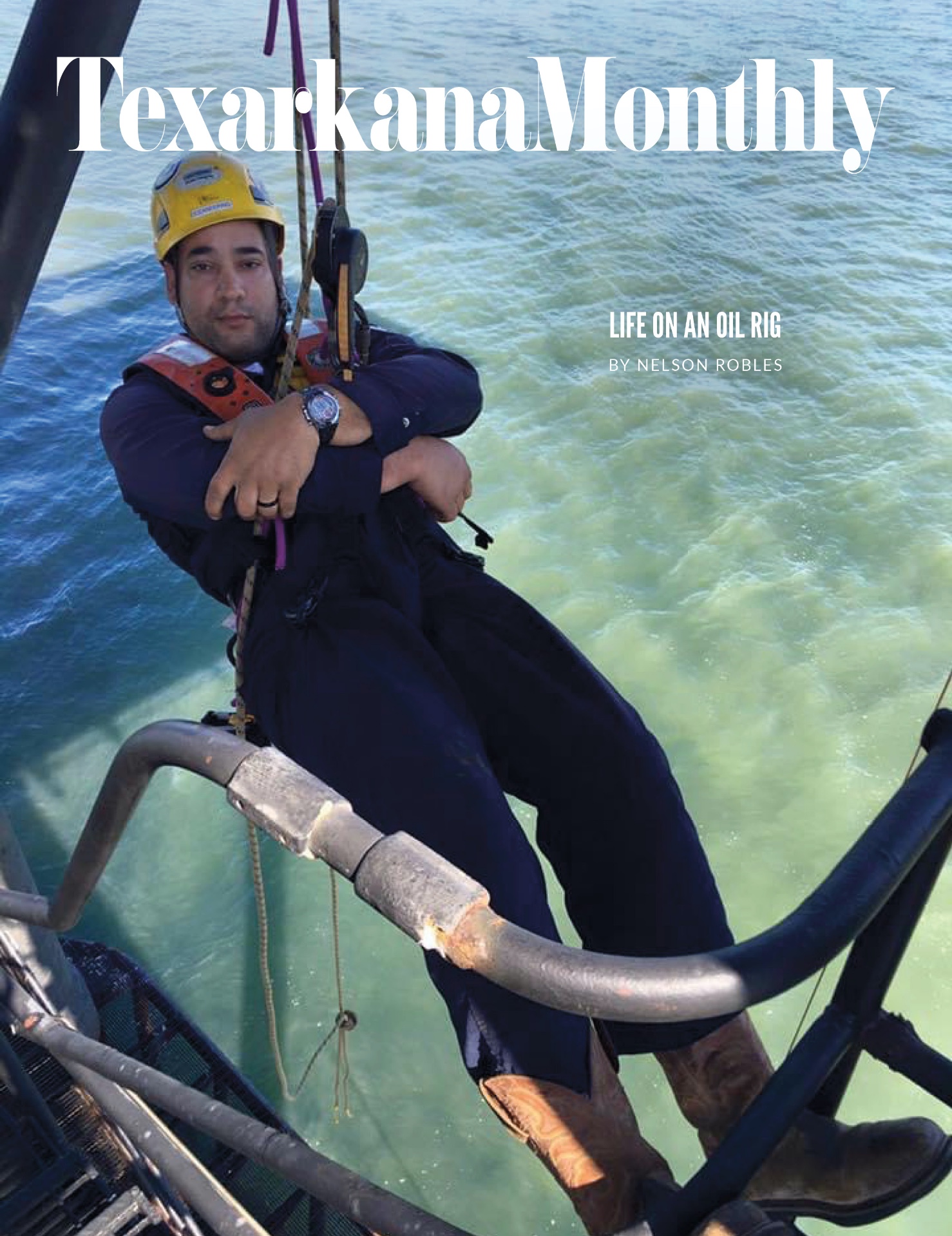

Life On An Oil Rig

I started working offshore on oil and gas platforms nine years ago.

My title is “inspector” but that covers a wide variety of tasks that make up my job. In a nutshell, I inspect piping and vessels and anything else oil and gas flow through, using various inspection methods to ensure the safety of the components. If I miss something or my inspection is not thorough, components can leak, crack, or in the worst-case scenarios, blow up, endangering the facility, personnel and environment.

I have been through more life-threatening situations than I like to admit to myself; a compressor fire on a platform, a fire that started in a welding area, and a high pressure (1200 psi) gas line explosion to name a few. I have been on boats that almost sank, and boats that have run up onto the rocks because of heavy fog at nighttime. However, I think a near helicopter crash takes the cake for my near-fatal events.

Normally, I get to the platform by helicopter, but sometimes we go by boat. Depending on how far out the platform is, it could be a 15-minute flight or even up to two hours. Mostly, I work in the Gulf of Mexico, but I have done jobs in Alaska and various other states. Some platforms are floating facilities, and some are fixed leg platforms. Fixed leg platforms are offshore platforms that are supported by thick steel cylinders filled with concrete that reach the bottom of the ocean floor. During the winter months, storms frequently pop up, making the platforms rock back and forth. Being a Sailor, it’s never been a problem for me, but it’s not uncommon for a newbie to experience some seasickness. In the winter, it is usually cold and miserable. Being surrounded by steel in the middle of the ocean with 60-70 mph winds doesn’t make for a good time.

Although some hold various engineering degrees, a college education is not required for this position. To become qualified requires hundreds of hours of on-the-job training, classroom training, and experience. You must also pass three grueling tests that comprise a test covering theory and general knowledge of specific testing methods, an open-book test covering particular codes which determine proper inspection guidelines, and a practical exam which tests competency in correctly identifying, locating, and reporting the faults you find. I am qualified to perform many inspection methods, and each of those methods is done using rope access.

Rope access is similar to what mountain climbers, or people that inspect wind turbines use. We rappel off the sides of the platform to access any area on the facility from the waterline, all the way to the top of the flare tip. At times, we are hanging hundreds of feet in the air performing one or more of these inspection methods. It’s fun stuff! Rope access training is a very physical course. There are three levels, level three being the highest. When you first start out as a level one, the training is just the basics of learning how to climb safely. Once you reach level three, which is where I am, you have to learn all the advanced rescue scenarios, including holding the body weight of yourself and another full-grown man while simulating various rescue methods.

Offshore life is not too bad. We have chefs and housekeeping services that do our laundry and make our beds. There are TV and game rooms. We have phones we can call home on, and WIFI we can connect to keep up with our favorite social media platforms. I’ve asked a lot of the old timers what they had to do before all these technological advances, and they told me they played a lot of cards and did a lot of fishing. We usually share the bedrooms with several other people, but at times you have your own room. The meals are great, often with a variety of food ranging from steaks and crab to sandwiches and chips.

Typically, I am gone about three weeks and then back home for about ten days. Occasionally, those three weeks can turn into up to two months, depending on whether I need to do back-to-back hitches. There really aren’t words to describe the feeling of not physically being with your family. Holidays, birthdays, pregnancies, and soccer games can be things that many parents take for granted. I have learned to spend my time intentionally, valuing the quality of the days I spend with them over the quantity. Nothing teaches you to appreciate your days quite like distance does. The months that my children from my previous marriage come from Manhattan, I try to stretch out the length between hitches as long as possible, squeezing in as many camping trips, vacations, and water balloon fights as I can. Every family is different, and the time I sacrifice away from my family is my way of providing for and nurturing our children.

We work long and grueling 12-18-hour days that can be difficult. Being away from family and friends only adds to that hardship. We have no off days unless storms make it impossible to work, so you normally work 14-21 days straight. Beyond the difficulties though, you get to see and experience many interesting things such as various marine life, including fish and sharks, as well as waterspouts and storms. Fishing is still a great way to pass the time. Aside from the yearly migration of sharks, the most interesting thing I have seen is 11 waterspouts at the same time. It made the Louisiana news and set a record for the most waterspouts! This life may not be for everyone, but for me, the challenges and the danger just add to the excitement of this unique profession. ![]()