Higher Purpose

November 11 is a special day in the United States as it commemorates the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, when in 1918, the first World War ended. Since that time, Americans have used this special day to honor all the brave men and women of this country who have answered the call as freedom fighters and who have given us the invaluable gift of security we sometimes take for granted. Randy Norfleet is among those gracious warriors who have selflessly sacrificed in and out of combat.

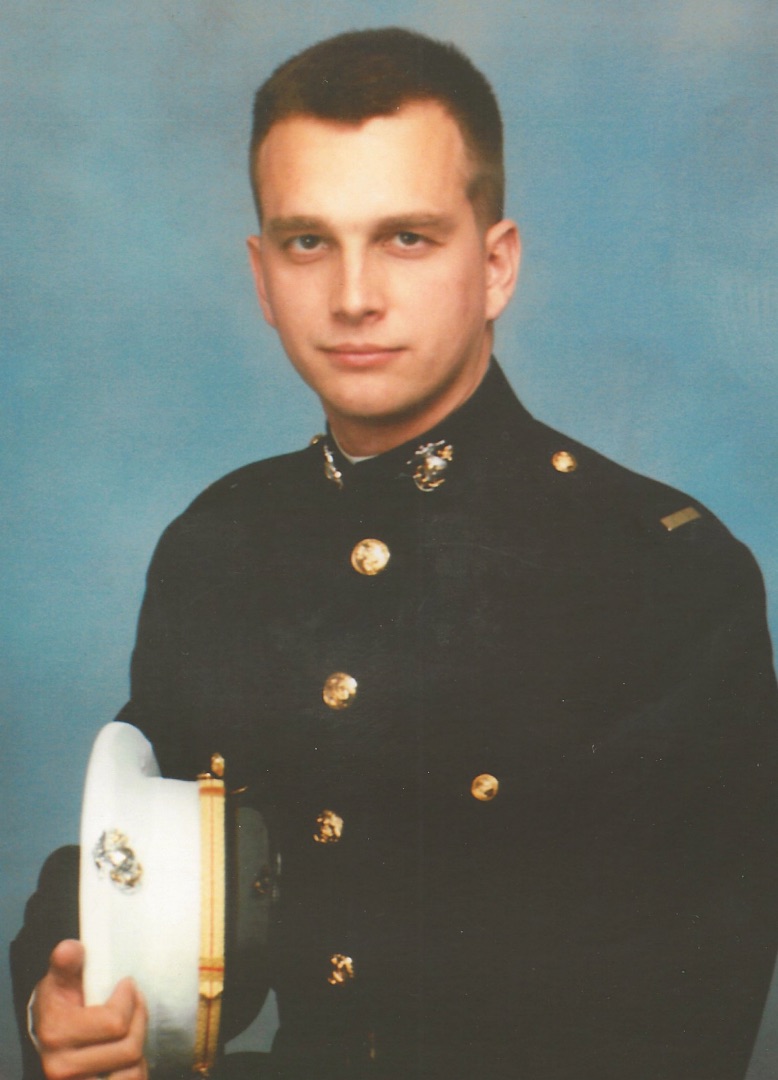

A retired Captain from the United States Marine Corps, Norfleet served as a pilot in Operation Desert Storm/Shield, Operation Laser Strike, Operation Eastern Exit and NATO Teamwork 92. “I was in the Marine Corps from November 1985 until October 1995,” said Norfleet.

“My sole reason for joining the military was to be a pilot,” he said. “I chose the Marines for two reasons. First, the United States Marine Corps has a Navy flight school contract which guaranteed I would be assigned to flight school and if I washed out of flight school, I did not have to stay in. Second, my grandfather was a Marine Rifleman in the Battle of Okinawa during World War II. After I joined the Marine Corps, my brother Jeremy joined, and then my cousin Scotty. So, it has become somewhat a rite of passage in our family.”

After completing The Basic School (TBS) in Quantico, Virginia, and Navy flight school in Pensacola, Florida and Corpus Christi, Texas, Norfleet began his military career. His primary military duties were as a KC-130 Aircraft Commander. Like countless other service members, his time in the military landed him in places and situations he never could have predicted.

Norfleet’s first combat experience was in Desert Storm from January through March 1991. Notably, February 26 and 27, 1991, American-led coalition air and ground forces attacked Iraqi military leaving Kuwait in what would later become known as the “Highway of Death.” “Major [Tom] Brehm and I spent seven combat flight hours refueling USMC F-18’s the afternoon and evening of February 26. This was during the ten hours of peak bombing time. After returning to base for crew rest, we returned the next day, February 27, to support continuing operations for another six combat flight hours,” he recalled.

“My second combat experience was in Peru. About three months after returning home from Desert Storm, Major Brehm hand-selected me for a covert mission to assist in hunting down Pablo Escobar in June 1991.” With a small crew, the two headed toward Lima, Peru. “Unbeknownst to us, there was a war brewing between Ecuador and Peru. It would eventually turn into the Cenepa War. Since we were in a military aircraft, the Ecuadoran Air Force scrambled a fighter intercept on us.” The intercept followed the flight until it reached Peruvian airspace and two hours later, they landed in Peru, where they were picked up in a blacked out Peruvian military vehicle. “The vehicle took us to the Crown Plaza Hotel and dropped us off at a back entrance. We were taken to the top floor level rooms. The entrance was guarded by armed Peruvian military. Early the next morning, we prepared our aircraft for flight. Once the aircraft was ready, a squad of Force Recon, Spanish speaking Marines, boarded the aircraft. As we moved into downwind, we started to take small arms fire. We expedited the landing. We taxied to the end of the runway and turned around for take-off. At this point, we opened the loading ramp and the Force Recon Marines disembarked directly into the jungle. We buttoned up the aircraft and took off at maximum climb.”

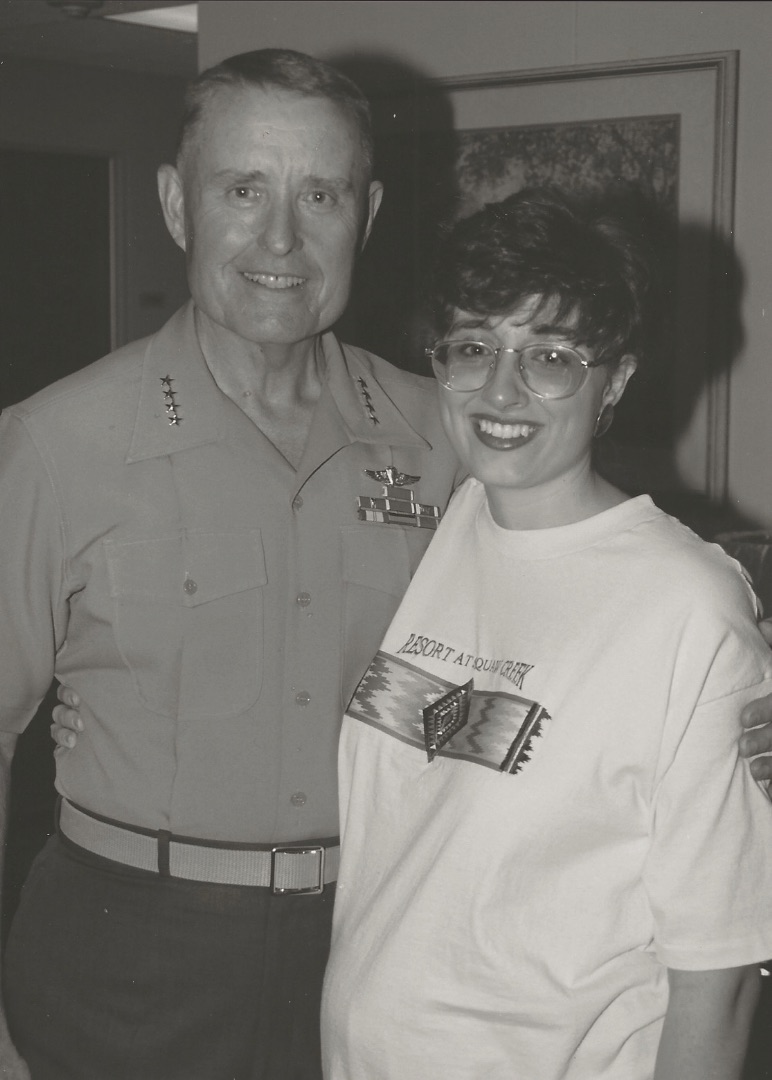

It is experiences like this that forge bonds between service members that are unlike other relationships. Men and women who put their lives into each other’s hands and trust each other to sacrifice all for one another, understand loyalty and commitment on an entirely different level. “Major Brehm was my Flight Lead during Desert Storm/Desert Shield and Operation Laser Strike. I had just graduated from my Replacement Air Group (RAG) when my squadron (VMGR-252) deployed to Desert Shield. Major Brehm had the dubious privilege of having the youngest and greenest pilot assigned to him. He only had a few weeks to bring a young man up to speed to face the trials of combat we would both face together in January 1991.” Their unique circumstances allowed them to see the best and the worst in each other. “He was not necessarily the nicest guy. In fact, you might say he was a little ‘crusty perfectionist and more than a little dramatic’. Through his crusty discipline, attention to detail and at times dramatic presentations, he crafted a young 24-year-old pilot into a combat ready Marine Aviator.” Sometimes in the crafting of well-prepared soldiers, a little behavior modification is necessary. Norfleet could also count on Major Brehm for a swift redirection when needed. “On day three of Desert Storm while he was briefing our next combat mission, I had the misfortune of briefly ‘resting my eyes.’ In the blink of an eye and flick of his wrist, the flight helmet next to him landed in my chest with a loud thud, to the snickers of flight crew all-around. Without missing a beat, he belted out ‘Wake-up Nodoz,’ and after that I never heard my given name again.” Norfleet was called “Nodoz” by all for the rest of his service. Regardless of Brehm’s sometimes gruff manner, the relationship between the two men was solid, which was proven when, just three months after Desert Storm/Shield, Brehm selected Norfleet for the mission in Peru. “We may not have been BFFs, but he trusted me when the rubber met the road,” said Norfleet.

On April 19, 1995, everything changed. Captain Norfleet, who was now the Officer Selection Officer (OSO) in Stillwater, Oklahoma, was in Oklahoma City for a prayer breakfast at a nearby convention center. After the breakfast, he stopped by the recruiting station at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building to see his commanding officer. Norfleet was stopped at a stoplight across the street from his destination when he noticed a yellow Ryder moving truck parked in the building’s loading zone. He witnessed who he would later recognize as Timothy McVeigh running from the truck and crossing the street. The scene seemed odd, but not strange enough to raise much concern.

Entering the building and making his way up the elevator to the sixth floor, Norfleet stopped and made a quick unanswered phone call. He then walked down the hall to visit an old friend. Suddenly, an enormous explosion ripped through the building and much of the structure collapsed. Glass and debris went flying along with Norfleet, who was thrown back against the West side wall. During the blast, he instinctively covered the left side of his face with his left arm, leaving it and the right side of his face vulnerable. His arm and right eye were riddled with the flying glass, and he began bleeding profusely. Within seconds, as support beams failed, the building crumbled and fell just a couple of feet from the spot Norfleet was lying.

He was briefly knocked unconscious, but quickly, after regaining his senses, he knew he could not wait there for help. His skull was fractured, his nose was broken and he was quickly losing blood from his eye and a severed artery in his left wrist, so he knew it was time to move. “Somebody had walked out of the building before me, and had left a blood trail. It was like a neon sign, a neon trail, right there on top of the dust and I followed the blood to the back of the building. Then, miracle of all miracles, all the stairs were intact at the back of the building,” Norfleet recalls. When he finally made it out of the building, into an ambulance and to St. Anthony’s Hospital, he had lost half of his blood volume and his blood pressure was 50/0. “If I had stayed in that building another five minutes, I wouldn’t be here today,” he said.

Norfleet was taken into surgery upon his arrival to the hospital, but before he was wheeled back, he had the presence of mind to relay his phone number to a receiving nurse who wrote it on her arm. The hospital was able to contact his wife Jamie, who was seven months pregnant at the time and sitting at home, willing the phone to ring with information. “I sank to my knees when I learned there had been an explosion at the Murrah building,” said Jamie. “All I could do was lift my hands and pray. God! I’ll take him any way I can. No matter if he’s hurt or even maimed. The kids and I need him! Please Lord, let him be alive. I’m begging You.” She quickly got on the road toward Oklahoma City, and after the pair were reunited, a lifetime of healing could begin, beginning with Norfleet’s retirement from the Marines.

In 1997, as a witness to Timothy McVeigh fleeing the scene, Norfleet testified as a key witness in his trial. He testified again in both of Terry Nichols’ cases and thanks in part to Norfleet’s testimony, both men were convicted of this horrendous act of domestic terrorism that killed 168 victims, including 19 children and injured more than 600 others.

For military families, it is not just the service member who is called to great sacrifice. “Jamie and I were married two months before I started The Basic School in Quantico, Virginia. Jamie was my partner through our entire Marine Corps career. She was there during the lonely nights I was on flight missions and deployed overseas. She was there raising our three children, mostly by herself. She was there during the anxious days I was in combat. She was there to hold our family together during the frightening day of April 19, the day of the Oklahoma City bombing and the ensuing days of recovery. The Marine Corps was as much her experience, trial and sense of accomplishment as it was mine. The Marine Corps didn’t affect our life, it was our life. Both of us are very proud of our accomplishments in the Marine Corps, but we’re glad the experience has come to an end.” This special family also includes three grown children, Matthew 31, Paul 28, and Morgan 26, who are all graduates of Texas High School.

Norfleet earned a Computer Science degree from Oklahoma Baptist University and an MBA in International Business from the University of Phoenix. He continues his career as a Sales Engineer and Partner with Testech, a Richardson, Texas based company which supplies electronic test and measurement equipment to industry-leading organizations across Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana and Arkansas. He joined this company in 2010 but has been selling test and measurement technology through other companies since 1995. “I’m a Partner at Testech and develop and sell integrated engineering test solutions for military programs like the F-35 Lightning II, F-22 Raptor, F-16 Viper, MV-22 Osprey and the new hypersonic missiles. For me, it was a natural progression [from military service] in several ways. As a Marine Aviator I was readily accepted in the F-35B and MV-22 programs since these are exclusively U.S. Marine Corps aircraft. Second, as a pilot, one of our primary skills is solving dynamic flight and mechanical problems at lightning-fast speeds. Since I was familiar with aircraft flight operations and systems, developing engineering test solutions for aircraft production and maintenance was an easy fit. As long as they’ll have me, I hope to stay engaged with the military aircraft programs which have given me a sense of accomplishment and pride in our country.”

As empty nesters, the Norfleets are excited about more time together and time with their two grandsons. Norfleet is also a committed Sunday School teacher at First Baptist Church Moores Lane and looks forward to growing his ministry there because just like through his military service, Norfleet has set his sights on a higher purpose.

Randy Norfleet’s Medals and Awards

Navy & Marine Corps Commendation Medal

2 Navy & Marine Corps Achievement Medal—OMPF

National Defense Service Medal

Sea Service Deployment Ribbon

2 Southwest Asia Service Medals with 2 stars

Air Medal—OMPF

2 Kuwait Liberation Medals

2 Kuwait Liberation Medals (K)

Meritorious Unit Commendation

Marine Corps Recruiting Ribbon

2 Humanitarian Service Medals

Navy Artic Service Ribbon

Cold War Medal