A Heart Made Whole

Heart-shaped candy boxes, heart-shaped balloons, heart-shaped cookies… February really is all about the heart. Every year, we use the fourteenth to celebrate those we love and express to them how much they mean to us. However, our heart obsession is not limited to the parties and confections of Valentine’s Day. February is also National Heart Month and serves to bring awareness to the importance of heart health and the millions across the nation who suffer with heart conditions. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared February “National Heart Month.” Over half a century later, the observation of Heart Month is still going strong. “Heart disease remains the single largest health threat to Americans—just as it was when LBJ was alive. Heart disease continues to kill more people each year than all forms of cancer combined.” according to heart.com.

For many people, it is possible to recognize heart abnormalities at birth, but for Megan Menefee it was not as obvious. She was 30 years old when she discovered a problem, a problem which to that point had caused her no real issues. It was almost by accident that her husband Dr. Kip Menefee, a Cardiothoracic Anesthesiologist, discovered something that gave him pause. “My husband, Kip, and I go snow skiing every year. It is our favorite hobby together. We had just returned from a ski trip in January 2010, and I wasn’t feeling very well. (It was) nothing major, just feeling a little under the weather with a sore chest and cough, possibly an upper respiratory infection,” Megan said. “I was kind of whiney and asked Kip to listen to my chest. To appease me, he put his ear on my chest thinking he was being funny. However, he leaned back with a bit of concern on his face and said, ‘Let me go get my stethoscope.’ He then listened and said, ‘Tomorrow, make an appointment to get an echocardiogram.’ I remember exactly, he said, ‘You have a harsh heart murmur.’ The crazy thing was that all throughout his medical school and residency, he would listen to my chest and heart sounds with his stethoscope to practice and never once heard anything out of the ordinary. Even growing up, my father, who was also a physician, would listen to my chest whenever I was sick, and he too never remembers hearing anything odd.”

Though shocked, Megan did exactly as Kip suggested. “The next day I made an appointment with my primary care provider for an echo. I tried not to panic, but instead stay calm and figure out what was going on.” Through that appointment, it was confirmed that Megan indeed had a heart murmur. Pressing the issue further, Kip reviewed a recent EKG she had gotten as a requirement for gym membership. He found an abnormality, that when combined with a heart murmur, typically indicates an Atrial Septal Defect (ASD), which is a hole in the wall between the heart’s upper chambers. “I was really only looking for sympathy and attention for feeling crummy, and he found something major.”

Megan then went to see a local cardiologist. She had an echo with bubble study done, which is used to identify potential problems with blood flow within the heart. For this study, saline mixed with a small amount of air, creating tiny bubbles, is injected into the patient’s vein. The mixture circulates to the heart. In a normal situation, the bubbles would be filtered out, but if there is a small opening between the chambers of the heart, the bubbles will move through the hole from the right chamber to the left, and this activity shows up on the echocardiogram image. Using this test, they determined the problem was between the upper chambers of Megan’s heart, showing a hole between the right and left atria. It was a very scary realization for her. “Up to this point I had held myself together, but when I saw the bubbles move across and the look on Kip’s face, I knew it was bad and I broke down in tears. This confirmed what Kip had suspected.” Megan could not believe what was happening. Would she really need open-heart surgery? “I was terrified,” she said.

Megan slowly came to terms with all the ways her life would be altered. “Kip and I had started talking about starting a family. I was told I absolutely could not get pregnant because I would likely not make it through childbirth. That was scary. The thought of having to have my chest cut open for a sternotomy in order to have heart surgery really scared me. I was young and healthy and didn’t want a big scar running down the middle of my chest.”

After much research, it was determined that an Amplatzer Septal Occluder would be the best course of action for treating Megan’s condition. In this procedure, a catheter is placed in a vein in the leg leading to the heart. The device used to close the hole is then run through the catheter up to the problem area where the procedure can be completed. This was great news to Megan because it would mean no major heart surgery. “I went in for my procedure in April 2010. After I woke, I excitedly asked if everything went ok and if the hole was closed. In my sedated fog, I could tell by the look on my husband’s face and the cardiologist’s face that it wasn’t good. I was informed the hole was too large and would need to be closed surgically.” Open-heart surgery would be necessary after all, and once again Megan was terrified.

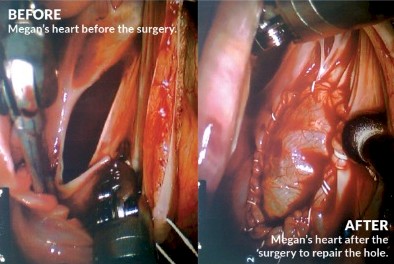

Kip and Megan decided to check into the possibility of robotic open-heart surgery. When it was determined that Megan was a candidate, her surgery was scheduled for September 14, 2010. The daVinci Robot, using its five robotic arms, was placed in the right side of Megan’s chest. “A piece of the pericardium, the sack that surrounds the heart, was cut to fit the size of the hole in my heart,” Megan explains. The ASD was very large and measured about four centimeters. While the heart was being repaired, Megan was placed on cardiopulmonary bypass for 21 minutes. “My entire surgery lasted about four hours,” she said. Following one night in the Intensive Care Unit, and then moved to a private room for one additional night, Megan was discharged from the hospital. Follow-up appointments were necessary, but after six weeks Megan was able to return to her normal activity with only five small scars on the right side of her rib cage. “You can hardly see any of them,” she reports.

“This experience definitely increased my faith. I can look back and see the path that God put me on and since then have trusted (Him) fully.” Kip and Megan are exceedingly grateful for the way things turned out. “Looking back, had we gotten pregnant before we made this discovery, the outcome may not have been good. Kip and I did eventually have one son, Asher, who is six now. We continue our annual tradition of snow skiing and this year plan to introduce Asher to the sport. Fingers crossed, he loves it as much as his dad and I do!”

The heart can be tricky and turning it over into someone else’s hands can be scary. In Megan’s case, however, things could not have turned out better. The research and development of new technologies that have occurred since that first National Heart Month in 1964 have made it possible for patients like Megan to experience tremendous outcomes. Without organizations like The American Heart Association and the dedicated medical professionals of this city and others across the nation, these advancements would not have been possible. The unsung heroes of this story and the ones closest to her heart are the members of Megan’s family and her closest friends who supported her and loved her through the hardest of days. Megan had the support she needed, medically and emotionally, and it made all the difference. When it is your heart at stake, it is those closest to you that truly fill all the holes. ![]()