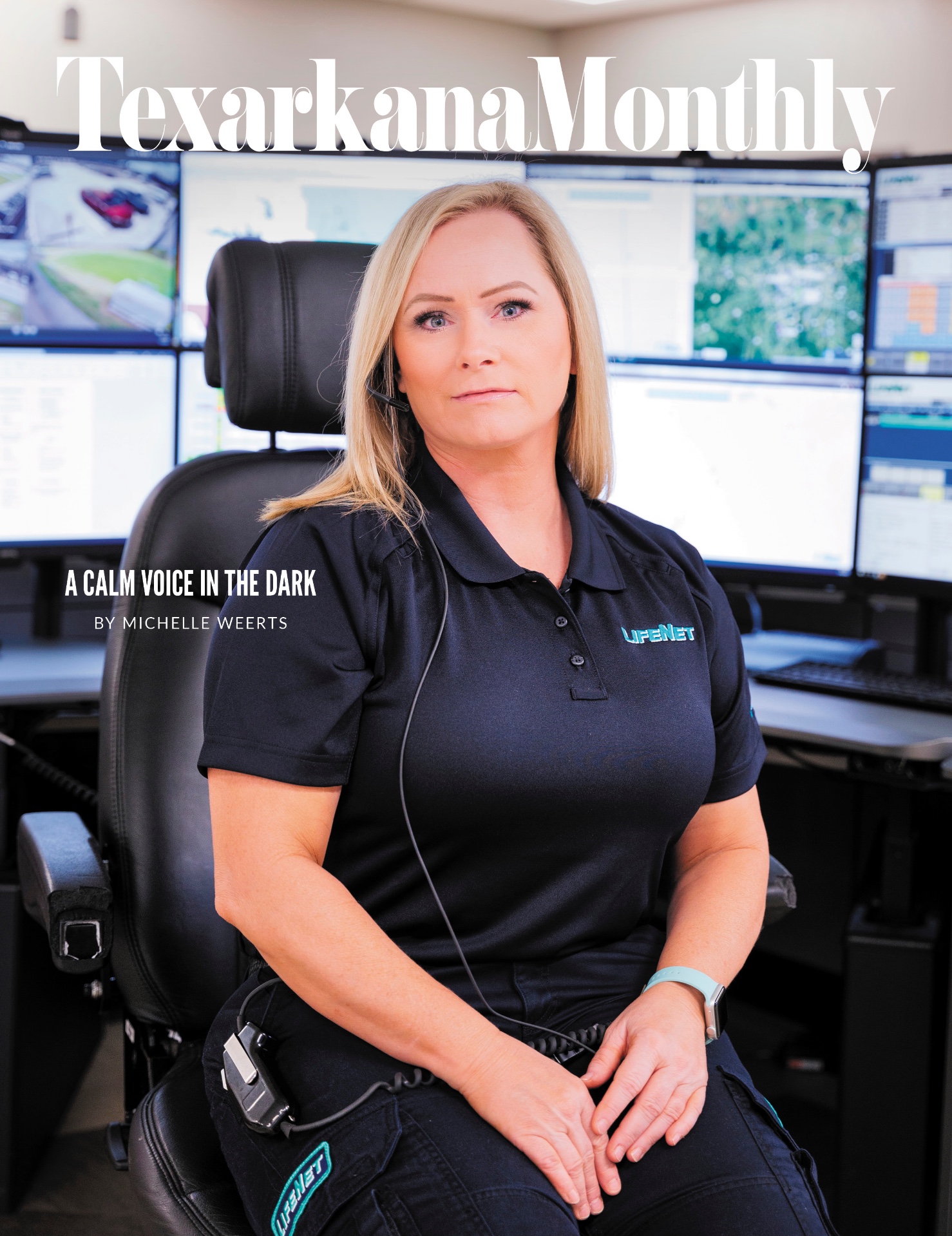

A Calm Voice in the Dark

The day starts as I walk into the dimly lit communication center for the beginning of a 12-hour shift full of unknowns. We work in teams as system status controllers. The call takers on-shift are already on the phones assisting callers who need our help with medical emergencies, while the dispatchers are on the radios talking to the ambulance crews. The room is full of dispatch consoles with six computer screens at each, showing area maps, our computer aided dispatch (CAD) program, phones and radio communication and other information.

As I sit down in my chair and place my headset on to start my shift, the off-going dispatcher gives a shift report from the previous 12 hours. Just moments into the shift, the 9-1-1-line rings. I place my hand on the keyboard. With a click of the mouse, I answer the phone with, “LifeNet, what’s the address of your emergency?”

Immediately I hear the voice of a terrified woman whose husband has collapsed and quit breathing. I enter the address into the computer so the dispatcher on the other side of the room has the information needed to dispatch the closest ambulance to the residence as quickly as possible. Simultaneously, I gather the information I need to give the caller proper instructions for helping take care of the patient prior to the arrival of our paramedics or first responders.

In this instance, the lady is instructed to lay her husband flat on his back on the floor and start chest compressions. With each compression, I have her count out loud. Methodically, she says, “one ... two ... three ... four ...” She is crying and begging, “Please don’t leave me, please stay with me.” I continue to encourage her to give chest compressions. “This will keep him going until our crews take over. Don’t give up,” I say. We keep working together, me as her telephone CPR coach, her as the bystander providing CPR, until the ambulance arrives to take over patient care. Once I am certain our crew is inside the house with her and has taken over patient care, I disconnect the line.

After more than 20 years of doing this, I still find myself shaking, anxious, cold and with a rapid heartbeat, as I disconnect the phone. It’s a byproduct of the adrenalin dump that happens after calls like these. I put my head in my hands, trying to process whether I did everything I could. I sit back and take a breath, not knowing if the next call I take will happen in seconds or minutes. I don’t have time to step outside for a breath of fresh air or to take a break before the next call rings. In mere moments, I must let go of those human emotions and redirect my attention to the new caller. This pattern will repeat itself for the next 12-hours of my shift in the communication center, stretching me and each of the other system status controllers working in the same room.

When my 12-hours are over, I will give my shift report, clock out, and get in my car to drive home. I won’t turn the radio on. I will simply soak up the silence and try to process my emotions. I find a place in my sub conscience to store them away as I separate work life from home life.

One of the hardest parts of our job is never knowing the outcome of a call. We learn to live without closure. This isn’t my story alone. It’s the same for all 9-1-1 telecommunicators. Each call is different. There are happy calls, such as assisting a father help his wife deliver their child and hearing that baby’s first cry and the joy in the father’s voice. I always ask with a shaky voice, “Is it a boy or a girl?” Everyone in the room is engaged and on the edge of our seats. Even after all these years, I still get emotional every single time I have the joy of assisting with the delivery of a baby. I wear that call like a badge of honor. But there are also the calls that are emotionally traumatic, including the ones where I have been the last voice someone hears before they take their last breath. Those are the ones that will always stay with me. I remember each one as though I just took it. However, I know that the last voice that person heard was the voice of someone who cared and knew their life mattered.

While the scenarios I shared are common, there is no typical day as a dispatcher. Television and movies often sensationalize the profession. It is better described as controlled chaos. I am often asked to describe what I do, by new people interested in working in dispatch. They want to know if we are also first responders, what training is required, and what it is like to work in a communications center.

First responders are often described by colors painted on a white version of the American flag. There is the “Thin Blue Line” for police and the “Thin Red Line” for fire. If you ever see the colors put together on the flag, you’ll also notice the “Thin Gold Line.” That line represents the emergency telecommunicators. Since September 2019, emergency telecommunicators have been categorized as “first responders” by the state of Texas, ensuring they have access to the same benefits and protections other first responders already had access to.

There is a lot of training involved in becoming part of that Thin Gold Line, and it can take up to a year for a new system status controller to complete it. Each dispatcher at LifeNet is certified as Emergency Medical Dispatchers (EMDs) through the International Academy of Emergency Medical Dispatch. Through this training, dispatchers learn how to give pre-arrival instructions over the phone, using the Medical Priority Dispatch System for Child and Adult CPR, childbirth, choking, bleeding control and other emergency situations. Our dispatchers are also CPR certified and are required to earn their Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) certification within the first year of employment.

One of the most common questions I get is, “Why did you choose to be a 911 dispatcher?” It was never my intent or goal to be in public safety. In 1998, I attended a CPR class with a friend. The director of the local communication center was in the class as well and approached me asking if I would be interested in sitting in the communication center to observe. I was a stay-at-home mom of a five-year-old daughter who was in school during the day, and I was interested in a part-time job. So, I took that opportunity to be a part of something interesting and exciting. With the first phone call, I was hooked. I knew I was where I was supposed to be. I found something I was good at and enjoyed. Now, 23 years later, I am still doing what I love. I am trained to do both dispatch and take emergency calls. However, my passion is taking the 9-1-1 calls. Connecting with the callers and knowing I have made a difference in someone’s life makes my heart happy.

The last thing I tell people who are interested in becoming a dispatcher is that it is an emotional job. It would be difficult to find the balance between work and home if not for the support of my family. Public service is a way of life in my household. I have multiple family members who serve in some capacity of public safety. My husband, who wears many hats in emergency services, is not only my best friend, but he also understands the emotions I experience. I am blessed to have that.

Although we are only on the phone for a short amount of time with our callers, we connect with them. They are our eyes and hands at the scene when we cannot be physically present to treat the patient. There will always be those calls that stay with you and you will remember the rest of your career. This job is both rewarding and challenging; it becomes a part of who you are and defines you. I can say with pride, there is no other job I would rather have than being the calm voice in the dark.